by Leonardo Lopez Carreno

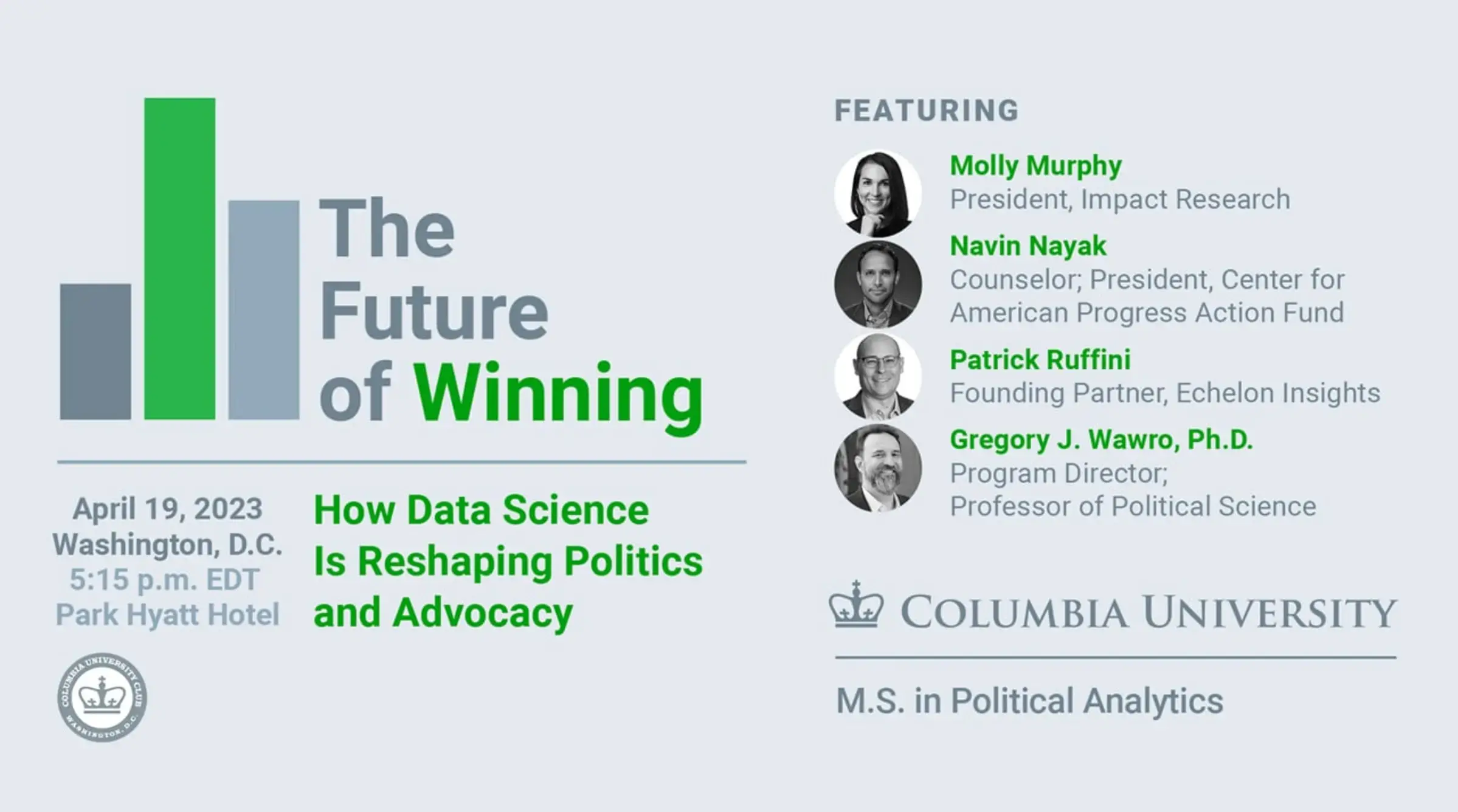

This past April, the Columbia SPS M.S. in Political Analytics program hosted the panel “The Future of Winning: How Data Science Is Reshaping Politics and Advocacy,” moderated by Forbes Tate Partners’ Doug Usher. Panelists discussed, among other topics, the challenges that polling is facing as a result of new strategies and the introduction of technologies such as AI into political analytics.

The panel:

- Doug Usher, Partner at Forbes Tate Partners

- Patrick Ruffini, Founding Partner at Echelon Insights

- Molly Murphy, President of Impact Research

- Navin Nayak, President of the Center for American Progress Action Fund

The following is an edited summary:

How is analytics central to winning in politics today?

Usher asked the panel members to define their idea of “winning” in the field of political analytics. Ruffini said that winning is “the marriage of two skill sets: the hard-nosed, traditional political knowledge combined with analytics that tell you what is doable or not doable within those parameters.”

“After the Obama 2012 campaign,” he added, “there was this huge surge of excitement in the belief that analytics held the key and you didn't need to really do traditional polling anymore, because they had cracked the code on how to measure the electorate.” That mindset, he explained, hurt Hillary Clinton’s campaign during the next presidential election.

Murphy, on the other hand, cautioned people not to lose sight of a more grounded perspective of winning. She asked the simple question: “Did you get more votes on this day?” She added that winning “is not incremental measures of progress; it is not coming up with a couple of different metrics to say we’ve moved things two or three points in this direction.”

Nayak, whose work is more focused on political policy and advocacy, shared a slightly different perspective on what winning in politics means. “We do some electoral stuff, and sometimes the base building is getting the right people in office,” he said, “but then once those people are in office, [it’s] thinking through how you are going to create the conditions that allow for policies to actually get enacted.” That mindset, he explained, is important for his organization, given that its audience is made up of “decision-makers,” such as senators and House members, rather than voters.

Polling: New challenges and combining data for advanced analytics

The panel then discussed the new challenges that polling is facing because of new technologies and industry practices. Murphy said that “it has never been easier to do polling and harder to do good polling” and that “you can do polls in a day, but it does not mean that those are the high-quality, rigorous polls that are going to stand up to methodological rigor.”

She then added that in order to obtain a more in-depth picture of voters, traditional polling data should be paired up with other data sets, such as behavioral data and polling on specific subjects, such as abortion rights or climate issues.

Murphy stated that, despite their attempts to keep on top of the trends, analysts can also gain insight from their failures. “You’re never going to be able to stay entirely ahead,” she said, “because you learn from who you miss, and from your mistakes and who’s falling out.”

She also advised political analysts and strategists to make sure that they consider the wide range of media through which people might respond to polls. “We still need to call people on their landlines,” she said. “It is a shrinking audience, but still one that exists. So if we cut that out, we would be dropping people out, and that would not be representative. Just like we need to reach people by text because there are people who won’t answer their phones.”

Balancing the work of AI technology and political strategists

Usher asked the panel about the benefits and drawbacks of using AI technology for political analytics and campaigning.

Ruffini said that a key question to ask AI vendors is, “How do you incorporate this in a workflow that then allows for the human being to take that analysis further, as opposed to having to completely redo the analysis because the person didn’t quite get something right at the beginning of the process?”

He added that one effective use of the technology would be to get the AI to do background research on a topic that is unfamiliar to a strategist so that they can take the work forward.

Murphy stated that AI could also help the process of polling by taking care of the “grinding work,” such as creating transcripts and reports from focus groups, thereby “allowing more time for thoughtful analysis.”

How can political analytics programs help job applicants to these firms?

Finally, the panel was asked about the current talent pool in the political analytics field, as well as the benefits a graduate program could provide those trying to find a job.

Ruffini said that 10 years ago, he would struggle to find data scientists and people with data skills to hire. “Today,” he said, “I get nothing but those applications, and it’s almost like an overcorrection.” He added that he wants “people who can ask good questions, who can write questionnaires, who have some experience with qualitative research and talking to people one-on-one in a research setting.”

Murphy added that there are two types of candidates: people who have a data background and are interested in politics but “haven’t been exposed to the political world,” and candidates who have a political background but are unfamiliar with data and shy away from using it.

She said: “The ideal applicant is someone who understands that data is not the answer; it is an indicator of how you get to the answer—and that sometimes what is clear in the data may not make any sense at all in terms of your end goals.”

About the Program

The Columbia University M.S. in Political Analytics program provides students quantitative skills in an explicitly political context, facilitating crosswalk with nontechnical professionals and decision-makers—and empowers students to become decision-makers themselves.

The final application deadline is June 15, 2023. The 36-credit program is available part-time and full-time.

For general information and admissions questions, please call 212-854-9666 or email politicalanalytics [[at]] sps [[dot]] columbia [[dot]] edu.