By Stephen Bodurtha

Steve Bodurtha, MBA, is a lecturer in the M.P.S. in Wealth Management program at the Columbia University School of Professional Studies. He teaches Investment Planning, a core course where students learn the essential principles of investing and how to apply investment skills to deliver and demonstrate value to clients. Bodurtha led Citi Private Bank North America’s transformation from banking and lending to investment and wealth services, earning the 2015 and 2016 Family Wealth Report Awards for “Best Private Client Investment Platform.” Prior to Citi, Bodurtha coheaded the investments, wealth management and insurance organization, and retirement business at Bank of America Merrill Lynch. He holds an MBA from Harvard University.

I had the chance over the December break to visit the architectural masterpiece in southwestern Pennsylvania known as Fallingwater.

This house is architect Frank Lloyd Wright’s iconic blend of nature and human artistry. It appears to grow out of the earth and float over a 30-foot waterfall with decks that have no supporting columns, projecting the structure over the stream and into the surrounding forest.

Source: National Endowment for the Humanities website

It’s beautiful, intelligent, impressive, and inspiring. And in too many ways, it failed the Kaufmann family, who commissioned and tried to live comfortably in it until it was donated to the Western Pennsylvania Conservancy, where thousands of visitors come annually to marvel at Wright’s creation.

“Because the house was directly over flowing water, it had problems with mold. The senior Mr. Kaufmann called Fallingwater ‘a seven-bucket building’ due to its leaks, and nicknamed it ‘Rising Mildew.’”

In a similar way, too many investment portfolios can have brilliant elements but end up frustrating and failing wealth advisors and their clients.

In our Investment Planning course in Columbia University’s Master’s in Wealth Management program, we learn to design, build, and maintain investment portfolios in ways that aim to:

*engage and deliver uncommon value to clients,

*support the family’s objectives,

*leverage multiple sources of investment expertise,

*use the right “building materials,” and

*enable adaptation as life unfolds and the world changes around us.

Easier said than done. Nonetheless, here are a couple of the tips we learn to apply in our course:

Client Engagement from the Get-Go

Too many investment journeys start with “What’s the best model?” Should I follow the endowment model? Risk parity? 60/40? And the list goes on.

This happens for a few reasons, not the least of which is the drive for scale: “Let’s get all our clients into a few good models that will allow us to grow our business efficiently and compliantly.” Another is the drive for differentiation: “You should hire me because I have a more expert mousetrap.”

This version of differentiation usually ends up painting the advisor and client into a corner when the model inevitably goes through a bad stretch. If you start the journey in the right place, a client relationship can survive such rough patches. But if you’ve claimed “the best model,” it’s really hard to change course without losing credibility.

Let’s be clear. It’s worthwhile for an advisor to have an understanding of this ever-evolving universe of portfolio models, in part because they may offer particular insights or elements that can be used as inputs or ingredients in a recommended portfolio.

And it’s important for wealth advisors to figure out where scalable, low-cost, tax-efficient investment solutions are the right choice and where more expensive, presumably higher-value “building materials” are worth it.

But all too often, the “best model” discussion casts the client as a passive receiver of alleged wisdom and sets up the advisor-client relationship for a fall somewhere down the road.

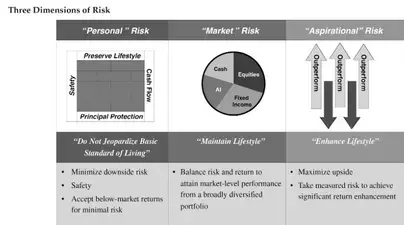

One antidote that graduates of our program have applied successfully is the Wealth Allocation Framework. That helps to frame the client’s investment journey as a decision not just about what asset classes to allocate to but also how to allocate personal resources, risk, time, and effort to the client’s various pursuits. It requires and leads to productive engagement with the client up-front that informs how a portfolio is designed, built, and made adaptable:

The Wealth Allocation Framework

Source: “Beyond Markowitz: A Comprehensive Wealth Allocation Framework for Individual Investors.” The Journal of Wealth Management, Spring 2005, by Ashvin Chhabra

Not All Investment Frameworks Are Equally Adaptable

A good investment architect develops a framework that is adaptable for different clients and for a given client as their circumstances change over time. The lack of adaptability in commonly used investment frameworks leads to too many dead ends in the wealth industry.

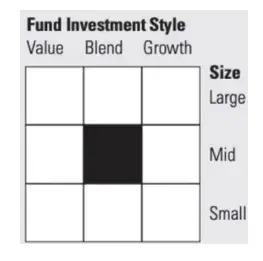

Here’s an example: The “size and style” method of allocating to equity funds has been a very popular method for building portfolios over the past 30 years. It’s rooted in groundbreaking research done by some of the greatest minds and practitioners in investment and wealth management. It presents a 3x3 menu of choices among small-, mid-, and large-capitalization stock funds, intersecting with “value,” “growth,” and “blend” funds (see figure below).

The Morningstar Style Box

Size and style investing has some really good things going for it, including broad acceptance, respectability, and scalability.

But it has its limitations. For example, with the increasing interest in private, alternative investments, the size and style method doesn’t apply readily to the world of private investments. Wouldn’t it make more sense to use a framework that can be applied across public and private investments?

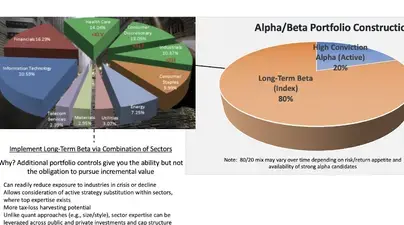

Much as size and style investing has overtaken sector-based investing as a portfolio framework in the wealth industry, there are reasons to think a sector framework is poised for a comeback.

Chief among these is its adaptability. It gives the advisor and the client an expanded set of portfolio controls that they can choose to use, or not, for more complex or simpler portfolios. It supports both public and private investing, active, index and risk management and tax-loss harvesting. Perhaps most important, it is intuitive. It makes a much clearer connection to the reality that a big part of equity investing is investing in businesses, not just buying a set of quantitative characteristics or, as Warren Buffett has put it, “blips on a screen."

The wealth industry may never catch up to Frank Lloyd Wright when it comes to turning investment portfolios into things of beauty. But it can do even more to make investment portfolios work a lot better for clients than Fallingwater did as a home for the Kaufmann family.