Through a two-part webinar series in May and June of 2021, Beth Fisher-Yoshida, Ph.D., Program Director for the Negotiation and Conflict Resolution M.S. program and Chair of Faculty at the School of Professional Studies, convened a panel of Asian American artists who are expressing their reactions to the recent spate of attacks against their community. “Art can be used to communicate, to protest, and to heal. Each of the artists on this panel will show their work and discuss how they are using their creativity to give Asian Americans a voice,” said Dr. Fisher-Yoshida. Below is a summary of the highlights from each artist’s presentation.

Yao Xiao: Documenting Unrest Through a Sketchbook

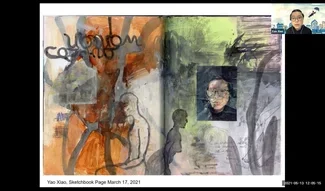

“This year we’ve been through a lot with the pandemic,” said Yao Xiao. “Since the beginning, there has been anxiety around being Asian American. The art I am presenting today is a series of sketchbook pages that I created after the Atlanta spa shooting which occurred in March 2021. My sketchbook reflects my feelings about this time. It’s become my practice this year.”

“This first one, I created the day after the Atlanta shooting. I came to the studio with a new feeling of grief and fear of being targeted as an Asian woman. My studio became my safe space in which to create, despite what was happening outside. I live in New York City and had to commute. That was challenging because the streets were a lot emptier, and during the pandemic, I did experience some verbal assaults. Nevertheless, I went to the studio every day, and the work I did is an expression of the emotions I felt during that period. I used a lot of strong colors to express what I was feeling. I also used some photo transfer techniques and baking soda. The work is experimental."

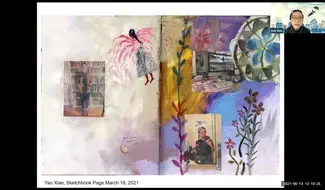

“In this section of the sketchbook, I created art that I felt affirmed me as an individual free of judgement."

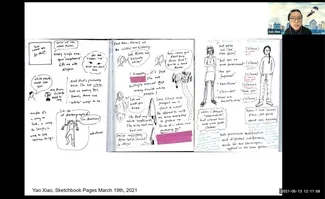

“I did this one a bit after the Atlanta shooting when news articles came out analyzing the presence of Asian women and the White fetish about us in our society. I started to feel that I could articulate my thoughts and added some writing to the art. Doing this prompted questions. For instance, what are the markers of queerness, or how is my body perceived in today’s environment? On the last page, I wrote some thoughts about the markers of individualism and how those are perceived on an Asian person’s body versus that of a White person. I imagine this will be a public piece at some time in the future."

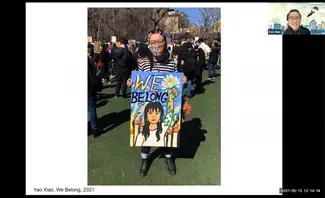

“I attended the Rally Against Hate in Chinatown in March. We made poster board protest signs. This is where my private art became public. It was very resolute. I wanted to show that there is courage in our art and in our community. The poster says, ‘We Belong. We demand to be accepted and protected in this society.’”

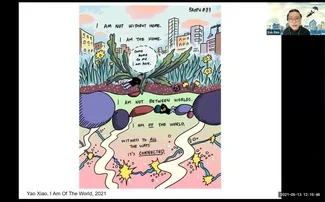

“The art features captions that say things like, ‘Come home to me; I am here,’ and ‘Witness to all the ways it’s connected,’ and ‘I am the home.’ I felt very strongly about Asian Americans being in between Whiteness and our own ethic community. So, I decided to publish this one, which was received very well.”

Cindy Trinh: “Not Your Model Minority”

“I am a photographer, photojournalist, activist, and organizer in New York City,” said Cindy Trinh. “I want to share how I’ve been dealing with the violence against our community. As an artist, my ambition was to share our struggles.”

“These two images are recent. ‘Fuck Your Bad Day’ was taken after the Atlanta shooting where six Asian women were killed. The slogan refers to the Sheriff who said that the shooter was ‘having a bad day.’ It begs the question, who gets to have a bad day? And who gets to commit murder over it? The statement about the shooter having a bad day was picked up by protesters. I saw a lot of signage around this. The sentiment was, ‘We have bad days too, and we’re not murdering people.’ The other photo shows an Asian woman holding up a sign saying ‘Not your Model Minority.’ This speaks to the fact that Asians are not a monolith; we’re not all the same. We have different experiences and different cultures. If you look at New York City, a lot of the people living in poverty are Asian Americans.”

“I’ve been documenting protests for about ten years. I didn’t like the way the media portrayed activists. You rarely see people just peacefully protesting because the media wants headlines, so they’re looking for controversy. In 2014, I started a project called ‘Activist NYC’ to document what I was seeing on the streets. This coincided with Michael Brown’s murder and the Ferguson riots, which caused protests across the nation.”

“I believe that art has the power to draw people in. There is a stereotype about us that includes things like, ‘Asians are only good at math and science.’ It’s difficult for Asians to break into the arts and creative fields, but we’re doing it, and reversing some of those stereotypes.”

“I’ve seen a lot. What I haven’t seen is a major movement among the Asian American community until now. Lately, there are faces that look like me out in the streets. For the first time, Asians are not silent or submissive. In fact, I see Asians being out, loud, and proud. We need to share our stories and our experiences in this country because, so often, we are a forgotten community. Now more than ever is the time for Asians to share solidarity with black and brown and LGBTQIA communities. Most importantly, we need to achieve safety for our women who have been so brutally attacked."

“I like this photo because it shows one Asian man in the middle of a crowd holding up the sign. The image isolates him while showing all those around him in support. To me, it speaks to the Asian American experience; we look alone, but we’re actually not alone."

“Another project that I’m doing is with actor and writer Christine Fang. After the Atlanta shooting, I wanted to do a project about Asian, non-binary women who have experienced being fetishized and harassed. As we know, after the shooting, the man who did it claimed that he had to kill these women to get rid of his sexual addiction. That sparked a conversation about all the stereotypes around how Asian women are perceived sexually.”

“We’ve never had a platform to discuss this until now. Christine and I decided to merge our skills, mine being photography and hers being acting. You can see the result on Instagram. I took photos of 16 participants, all Asian-identifying, both women and non-binary. I took their portraits and then we sat down and interviewed them and got their stories. Christine then took parts of each story and wrote original monologues and each one is voiced by an Asian actor. On Instagram, you can see the portrait and hear the monologue.”

“The stories are powerful retellings of what many of us have to deal with as Asian people, whether it’s in dating experiences, work or social experiences, or just dealing with people on the street who harass or threaten us. The collaboration between myself, Christine, and those who shared their stories has been empowering. Our hope is that art and the ability to share it on social media will resonate with others and give Asians the chance to empower change.”

John Lee: An Asian American Experience with Southern Roots

“I am an artist, illustrator and educator,” said John Lee. “I teach in an adjunct role at Queens College. I live in New York, but I grew up in Memphis, Tennessee. The work I want to show is a reflection of who I am as Asian, where I grew up, and my family’s immigration story. All of these things bleed into your psyche, whether you like it or not. My art of late has been around anti-Asian racism and white supremacy.”

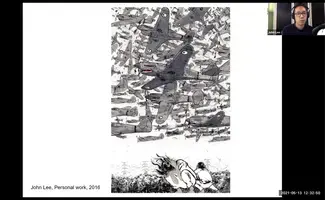

“This is work I was doing in grad school. At the time I was learning about Asian American history, and becoming increasingly aware of how much of that history was born of violence. For instance, there is a historical idea that Chinese Americans earned the right to be US citizens because they fought on the side of the US in World War II. Or that Japanese Americans retroactively proved their loyalty to the state by undergoing the trauma of mass incarceration. There’s a kind of trial that happens with Asians in relation to this country. And it’s born in each case from violence. So, when we see a spike of violence like we did this year, it’s not unexpected.

The issue becomes, how do we deal with it now versus how we dealt with it in the past?"

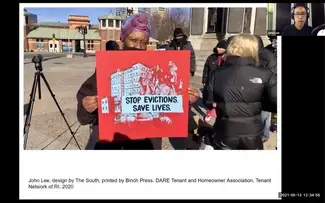

“This past year, I’ve partnered with various groups. One is DARE, local activists in Rhode Island who support eviction moratoriums and rent payment cancellation. I’ve also been doing work with BLM in Minneapolis, supporting various police abolition movements. I create imagery and messaging that conveys the story or catches eyeballs online. If I can get attention and communicate clearly through a compelling drawing or design, then I’ve played a small role connecting art and activism."

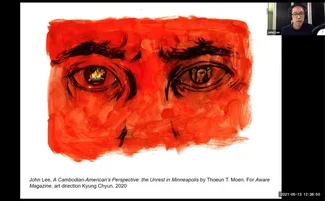

“This piece for Aware Magazine focuses on a Cambodian American creative Thoeun T. Moen, who lives in Minneapolis. My editor Kyung Chyun, who is Korean American invited me to explore the intersectionality around the BLM protests for George Floyd. Thoeun talks about being Brown, queer and being pulled over by the police. He basically said, ‘There are things about the US that I understand more clearly through the lens of Black America than I do through the blurry lens of being Asian American.’ There was a level of solidarity that was interesting to read from a Cambodian standpoint. It’s definitely something I’ve thought about as a Filipino American."

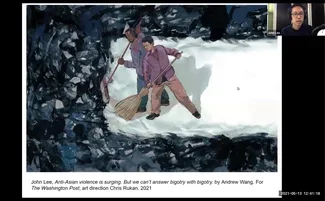

“I did this illustration for a piece by writer Andrew Wang for The Washington Post. He wrote about one of his uncles in Texas in the late ’90s who came to the US from China only to bes carjacked and killed. The story addressed the trauma that his family experienced, and how such a violent incident shapes your opinion of what America is really like.”

“This story dovetailed with my own family’s history. I’m from Tennessee. My father’s family has been there since the late ’50s. Memphis is, of course, the place where Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was killed. It’s a heavily racialized city, and I lost an uncle during the unrest that occurred after Dr. King’s murder. Tensions exist between Asian Americans and other racial groups in the South. For instance, there’s this weird dynamic of Chinese American grocers in Black neighborhoods; on the one hand, catering to and being a part of those communities, but on the other, wanting to leave eventually for more resourced white neighborhoods . For me, those tensions define being raised Asian American in the South.”

“When I did the illustration for Andrew, I think I really understood his feelings about racism and xenophobia. He wrote that our response can’t just be anger and resentment; it has to be constructive. We have to build bridges between our communities. Expressing these feelings on The Washington Post was surreal. If you had told me five years ago that I would have dealt with such nuanced ideas on such a large platform, I wouldn’t have believed it.”

“Here is a picture of me holding up an illustrated sign that says, ‘Solidarity Forever.’ I know it’s simple but I thought it was important to highlight solidarity between different communites within Asian America; in that moment, women, undocumented immigrants, and sex workers.This art was not done for commercial intent We simply stood out there and made ourselves known. In the US, there is always a constant awareness around what kind of space you take up according to your race. At a protest decrying racism, amongst your community, taking up space becomes a powerful moment, psychically.”

Connie Sun: People with No Power Going After People with No Power

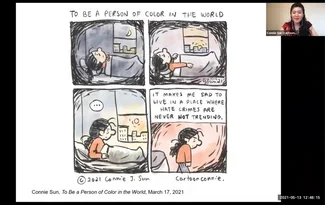

Connie Sun is a cartoonist and writer, who worked for the Columbia University NECR program for more than 8 years, from when it first started. It was also where she began her daily cartooning practice, as an exercise in self-awareness and reflection. “I would get up every morning before going to work and draw a cartoon ; it was my way of processing my emotions and making sense of things around me.”

“How have I been processing this moment in US history? Like Yao, I keep a sketchbook and this first cartoon is one of the pieces I did the day after the Atlanta shooting. It wasn’t something I wanted to think about, but it also felt essential to. When something like that happens, it hijacks your emotions. It’s a moment of trauma when you’re forced to reckon with [an event] whether you’re ready to or not. I went to bed the night of the shooting and woke up with the text of the cartoon at the front of my mind, ‘It makes me sad to be in a place where hate crimes are never not trending.’ What happened isn’t unique to the Asian community, but it’s what’s trending for us right now.”

“The art I’ve been creating is raw and not something I’m going to put in a portfolio of my work. I had to process what felt like a very personal attack on people who look like me. What struck me about the Atlanta attack was that it felt like nobody cared [or was paying attention in the days that followed]. I truly felt alone and isolated at that moment and I understood that this is personal, this is emotional [not distant or second-hand], and we are not the only ones [who have experienced this”. out to me to see if I was okay, but my White friends did not. Something clicked at that moment: ‘If you feel unsafe, then it is everything.’”

“If you don’t feel it firsthand, there is more distance. Or there is [unexamined] discomfort: how do you start these conversations? The only thing I could process at the time was, ‘This doesn’t feel good [that some aren’t seeing] what’s happening to the most vulnerable in the Asian community, those among us with the least power; it’s people with no power going after people with no power and that is almost the [whole] story of racial division in this country.”

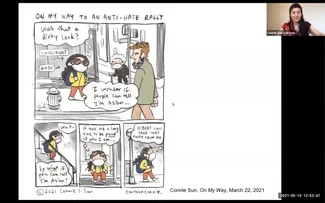

“I drew this cartoon [titled] ‘On my way to an anti-hate rally.’ Being Asian right now, you feel a bit paranoid because, on the one hand, things are different because of the pandemic and, on the other hand, if people look at you a certain way, you don’t know what that means. You think, ‘Was that a dirty look? Can that person tell I’m Asian with a mask and sunglasses on?’ In this process, I had a similar reckoning as Yao did and I thought, ‘Wait a minute; I don’t need to hide who I am. I belong here, and I am proud. I wasn’t always proud to be Asian, but I am proud [now]. It’s something I worked very hard for, even though I didn’t grow up with that as an example. I earned [where I am today], and nobody can take that away from me. That’s the sentiment of this [cartoon] ."

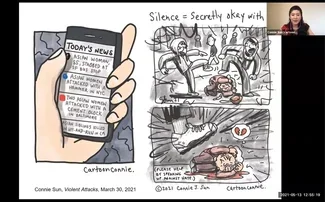

“This next set of cartoons is not necessarily “nice,” crowd pleasing art. But this is what it feels like. If you’re Asian, events in the news right now are amplified. The art shows [an elderly Asian woman being attacked while bystanders look on]. When people are silent, it feels like they’re okay with it. After this incident that I’m referencing in the cartoon, all I could think was, ‘Please help by speaking up against hate. It was just my internal plea: please just see what’s happening.’”

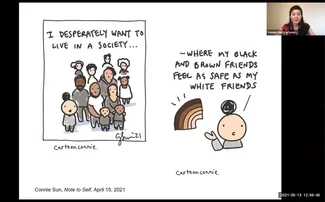

“I drew this cartoon a month after Atlanta. It says, ‘I desperately want to live in a society where my Black and Brown friends feel as safe as my White friends.’"

“This was my wish on a bleak day. I processed a lot of this inwardly through my art. My approach to activism is very inward.This is also the first opportunity I’ve had to talk about this with my parents. These are not conversations that happen often enough in immigrant families and this opens up a channel to talk about [difficult] topics. My learning is that, in crisis, there is potential for change and that small change counts. This is where I’ve come after [processing some of] the grief, anger, and trauma."