When Negotiation and Conflict Resolution faculty Dr. Beth Fisher-Yoshida and Joan Camilo Lopez witnessed civil unrest take hold across the United States last summer, they saw opportunities for longer-term social transformation based on their fieldwork in a similar context: Medellín, Colombia. Once a city internationally characterized by violence sustained by complex, interlocking economic, social and political factors, Medellín has enjoyed a reputation of greater safety in recent years. A winning combination of community-led action, local knowledge and theory-based strategy are part of the reason why, says Dr. Fisher-Yoshida and Lopez.

In Redefining Theory and Practice to Guide Social Transformation: Emerging Research and Opportunities, available now, Dr. Fisher-Yoshida and Lopez discuss the ways in which different communities that had once been engaged in violent conflict had found ways to reconcile and build peace despite a civil war that spanned decades and related ongoing challenges. They explore case studies from Medellín which organizers and individuals invested in social transformation in the U.S. may find relevant and applicable today.

Watch the entire conversation between the NECR faculty members and co-authors above.

“Many of the people with whom we work in Medellín are grandsons and granddaughters of people who were displaced from rural areas due to conflict between different groups, including the government and paramilitary groups,” said Lopez in a recent conversation with NECR Academic Director and co-author Dr. Fisher-Yoshida. But in their interviews with local leaders, Lopez and Dr. Fisher-Yoshida discovered a surprising pattern: many community leaders in Medellín, especially young people, focused on proactive peacebuilding rather than the relatively recent instances of violence and injustices in the past.

“It wasn’t a denial of what happened in terms of violence and deprivation, but it was a choice that they were making — even if it wasn’t a conscious choice — to focus on other things that were happening,” said Dr. Fisher-Yoshida. A departure from traditional academic publications, the book equally positions academic theories and local knowledge. Dr. Fisher-Yoshida and Lopez, who’s a part-time lecturer in Columbia’s M.S. in NECR program, have been conducting fieldwork in Colombia for about six years, working with local organizers and community leaders to build and sustain peace after and in the midst of ongoing conflict.

“[We did not] dictate what we think they should do because we’re not part of the local community. We don’t have the local knowledge; we have other types of knowledge from the academy and from our own practice in other communities and organizations. We wanted to see how we could work with them to enhance what they’re doing. Many of them were doing interesting things through the arts,” said Dr. Fisher-Yoshida.

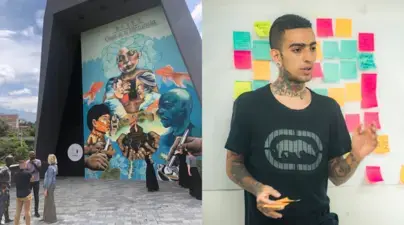

In an ongoing partnership with local leader Wilmer Martinez, one strategy the NECR faculty offered was the Coordinated Management of Meaning (CMM), a communication theory created by American academics in the 1970s. Taking advantage of the local knowledge and proximity to or membership in the communities with which he was working, Martinez incorporated CMM into his approach, collecting community members’ various understandings of reconciliation. “He brought in a group of different graffiti artists to then work with the community members to picture, visually, what reconciliation would look like” recalled Dr. Fisher-Yoshida. The interviews culminated in a collective understanding of how to harmonize a community of groups that had previously engaged in violence against each other and a large mural outside the Museo Casa de la Memoria, which debuted last Fall. “It’s just a testament to people being able to transform their image of violence and really visually and verbally depict what reconciliation meant to them,” Dr. Fisher-Yoshida said.

Lopez added, “These youth leaders who were looking to transform their communities were not memorizing or telling the story of what made their families leave those rural areas… their focus was more on the peaceful responses to the conflict.”

NECR faculty members Joan Camilo Lopez and Dr. Beth Fisher-Yoshida have been working in partnership with youth leaders in Medellín for six years, offering academic theories such as dynamical systems theory to map complex, often interlocking dynamics.

Incorporating the Coordinated Management of Meaning theory, Medellín residents participated in workshops to collect their various understandings of reconciliation. They culminated in a collective understanding of how to harmonize a community of groups that had previously engaged in violence against each other and the Mural of Reconciliation outside of the Memory House Museum. Graffiti artist Burro (right) participates in a workshop with residents.